Prologue

There is no such thing as a pure or adulterated food on its own. We have to make it so. Pure food comes from pure people, it is a matter of trust and confidence. This book is about how people drew the line between pure and adulterated during the pure food crusades of the later 1800s. Today’s world is different from that of our nineteenth century forebears in so many ways, but the challenge of policing the difference between acceptable and unacceptable practices remains central to daily decisions about the foods we eat, how we produce them, and what choices we make when buying them. The legacy of the pure food crusades resonates with us still, having put a regulatory framework in place that structures our approach to patrolling the border between pure and adulterated.

Chapter 1 The Appearance of Being Earnest

The introduction brings us the story of Alfred Paraf, a dashing Frenchman known upon his 1885 death as “foremost in the ranks of the world’s swindlers.” With chemical training from his dye- making father in the Alsatian town of Mulhouse, a cache of patented inventions, and, to quote the New York Times, “the suave address of a gentleman,” Paraf’s story of trans-Atlantic charlatanism—from France to Scotland to New York to San Francisco to Chile—begins the story of pure and adulterated foods with reference to trust, deception, and the confusing appearance of reality in a new world of manufactured goods.

Part I: The Culture of Adulteration

Chapter 2 Surfaces and Interiors

As the first of two chapters in Part I: The Culture of Adulteration, this canvasses the deep history of adulteration to set up the debates about character, sincerity, and authenticity that suffused the mid-nineteenth century. Distance matters as a way to understand the confusion and mistrust, but cultural distances between people were as dramatic as geographical distances between producers and consumers of food. The problem of knowing the difference between the surface of a food and its interior, “real” identity was shaped in part by the problem of knowing the difference between the surface of a person and their true interior character.

Chapter 3 Household, Grocer & Trust

Adulteration is age old, but a multitude of changes in the later nineteenth century gave the problems a different public status. New means of food purchasing, particularly a nascent grocers’ empire, were key in this regard. The urban grocers’ market was a front line in the battle against adulteration. It was a place of interaction in the network between producers and consumers and a space of exchange between the trusted and suspicious. Chapter 2 put its lens on the border between the surface and interior of foods. The relevant border of this chapter is the one between inside and outside the body at three levels of a Russian nesting doll, that of the body politic, the household body of kitchens and homes, and the individual body.

Part II: The Geography of Adulteration

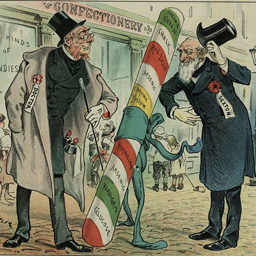

Chapter 4 Margarine in a Dairy World

This chapter examines oleomargarine and butter as the first of three case studies in Part II: The Geography of Adulteration. It details the ways margarine was the product of a changing agricultural landscape. The story of margarine is intricately tied to the history of butter, which means it is about cows and the dairy industry. But it is also tied to cows of the nascent slaughterhouse world—margarine’s beef fat was a byproduct of the packinghouses of Cincinnati and Chicago. The chapter thus brings the testimony of farmers, dairymen, meatpackers, and grocers to bear as they weighed in on the growing networks of production tying cities to dairy lands and the Midwest to the east coast, the south, and to export markets around the Atlantic world.

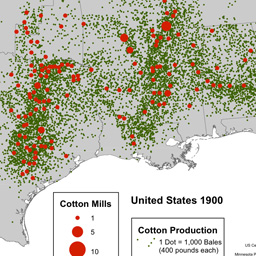

Chapter 5 Oil Without Olives and Lard without Hogs

In a Southern post-bellum economy, the new profession of the seed crusher extracted oil from formerly discarded cottons seeds for what they called “the Cinderella of the New South.” It was the neglected stepchild now shining for its economic potential. That potential first came as a substitute for olive oil, where southern crushers brokered deals with Italian olive growers, who then mixed it with their product and sent “pure” olive oil back to the ports of New York. The cottonseed crushers also developed supply networks with meatpackers in Chicago, who used it as a lard substitute. This chapter draws the geography of the upstart adulterant by mapping the new relationships between southern cotton fields, Midwestern packinghouses, and global markets.

Chapter 6 Glucose in the Empire of Sugar

The saga of “Professor” Henry Friend’s Electric Sugar Refining Company angered investors and bemused readers in the 1880s. Friend was a swindler. He sold sweetener made from starches in a process that he never explained to his investors, claiming secrecy, an Edisonian connection, and fear of theft. After his scam was exposed in 1889, newspapers raced to compare it to those of the wily Alfred Paraf. Producers would call the product “glucose” at a time before the term referred to a monosaccharide known as blood sugar. This chapter uses Friend’s con as an entry to map the geography of fake sugar and sweetener production, tracking their production, distribution and status in the landscape of adulteration.

Part III: The Analysis of Adulteration

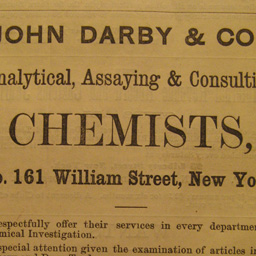

Chapter 7 Analysis as Border Patrol

This is first of two chapters of Part III: The Analysis of Adulteration. It puts the focus of pure food debates on the chemists, analysts, and other public health officials who responded to the proliferation of suspected adulteration. Chemists and public health analysts responded to changing agricultural patterns and commercial endeavors in articles, ads, and exposés in journals and trade papers, grocer’s publications, and domestic science magazines. The chapter looks to the regional and household scales to place the ambitions of chemical analysts into a world of domestic chemistry and everyday life, the world where housewives, families, chemists, and government officials sought to police the legitimacy of food purchases, preparation, and eating in a time of adulteration fears.

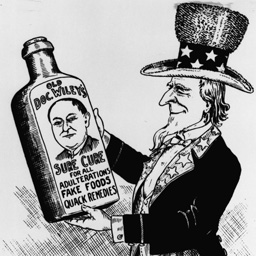

Chapter 8 Food and the Government Chemist

Where Chapter 7 takes the regional and household scales at its focus, this one telescopes out to a broader political level to attend to commercial-level chemistry. It brings the main narrative to a close in the early 1900s, when federal-level authority of scientific analysis and quantitative measures of food followed from assumptions about food health, purity, and adulteration of the prior half century. Here we get Upton Sinclair, the ultimate passage of a pure food bill, and the bureaucratic and institutional success of the Progressive Era in the establishment of the eventual FDA. The chapter folds the federal efforts together with the new consumer world of grocers, agricultural fields, and foods. By 1906, what mattered was not a food’s environmental cultivation (a process embodied by agrarian labor) but the fidelity of the chemically detected items on a label to the item inside (a product-based assessment). Purity had become a scientific concept.

Epilogue The Persistence of Adulteration

Conditions change, adulteration remains. It was a problem in the past, it is a problem today, and it will be a problem of public concern tomorrow. This is mainly because our terms for what counts as “pure” change with political and cultural conditions, as do our techniques for patrolling the border between purity and adulteration. More important for a healthier future is to engage with the environmental process of agriculture and food production, to create ways of broadening the experience of food beyond consumer metrics alone, and to build attention to culinary, ecological, and other ethical factors in our debates about organic principles, genetic modification, additives, and synthetic chemical processing.